Historical and Industrial Heritage IJmuiden

Experience Old-IJmuiden is a 3 ½ mile (5.5 km) walk which takes you along 25 historical and cultural places of this former fishing neighbourhood

Solid information boards show photo’s and information about Old-IJmuiden in the olden days; places and buildings that have disappeared or changed. On this page you will find more information in English about places along the route, with many photo’s and stories.

The Old IJmuiden Experience

The Old IJmuiden Heritage walk is part of the story project Experience Old IJmuiden. Stories have been collected about the history of Old IJmuiden, from the construction of the North Sea Canal in 1876 until today. The stories were published in the IJmuider Courant in 2014-2015 and in a book, Beleef IJmuiden (Experience Old IJmuiden). The project is commissioned by the Velsen Welfare Foundation and the Stories Connect Foundation.

Harbour Head and Fortress Island

Because IJmuiden was the only North Sea port between Hoek van Holland and Den Helder, fishing boats from miles around tried to find shelter in the North Sea Canal estuary, between the jetties, thus obstructing the passage to Amsterdam. This is why the Vissershaven (Fisher Harbour) opened in 1896, thus creating the Harbour Head.

The fortress was built between 1881 and 1888 and is the largest of the Defence Line of Amsterdam, which is a UNESCO World Heritage site. The fortress became an island in 1929 and was also part of the Atlantikwall in World War II.

The locks, ice factories and cold stores

In 1876 King Willem III opened the North Sea Canal, the Kleine Sluis (Small lock) and the Zuidersluis (Southern lock). The Noordersluis (Northern lock, 1928) with its length of 400 metres, width of 40 metres and depth of 15 metres was the largest in the world.

Until around 1900 fish were preserved by filling them with salt; from then on ice was used for this purpose. The ice was obtained from ponds of large estates or even imported from Norway. In more modern times the ice was made in ice factories like Koelhuis IJsvries.

Sluisplein, lockkeepers houses and pilotage

The oldest buildings of IJmuiden line the Sluisplein. At the end of the 19th century ten staff dwellings, seven government buildings and warehouses for pilotage were built there.

From the harbour office at 3 Sluisplein the lockkeeper had an excellent view over the locks. On the corner of Sluisplein and Visseringstraat the old Bell Tower (1896-1925) is situated. On the island beyond the Southern lock houses for staff of the locks and the power station were built between 1909 and 1917, as well as land batteries for the Dutch World War I coastal defence.

Hotel Augusta

Hotel Augusta was built in the year 1907 and commemorates the name of Augusta Victoria, wife of the German Kaiser Wilhelm II. The hotel was originally owned by the Heere family. Unlike a large part of IJmuiden, Augusta ‘survived’ World War II. All these years Augusta remained in possession of the Heere family. Their children ran Augusta until the current owners, John and Monique van Waveren, took over the hotel in 1984. At that time the building was a mere ruin. The restaurant part remained original. The Salon Café used to house tobacconist Dorresteijn, and was later bought by poulterer Onrust, locally known as ‘Arie Kip’. After several years the adjacent building (now called the Orange Lounge) was added to the hotel. On the current location of the reception, the breakfast room and the Crown Hall used to be the haberdashery of the Botman family. On the corner was the Baptist Community Centre.

Thalia

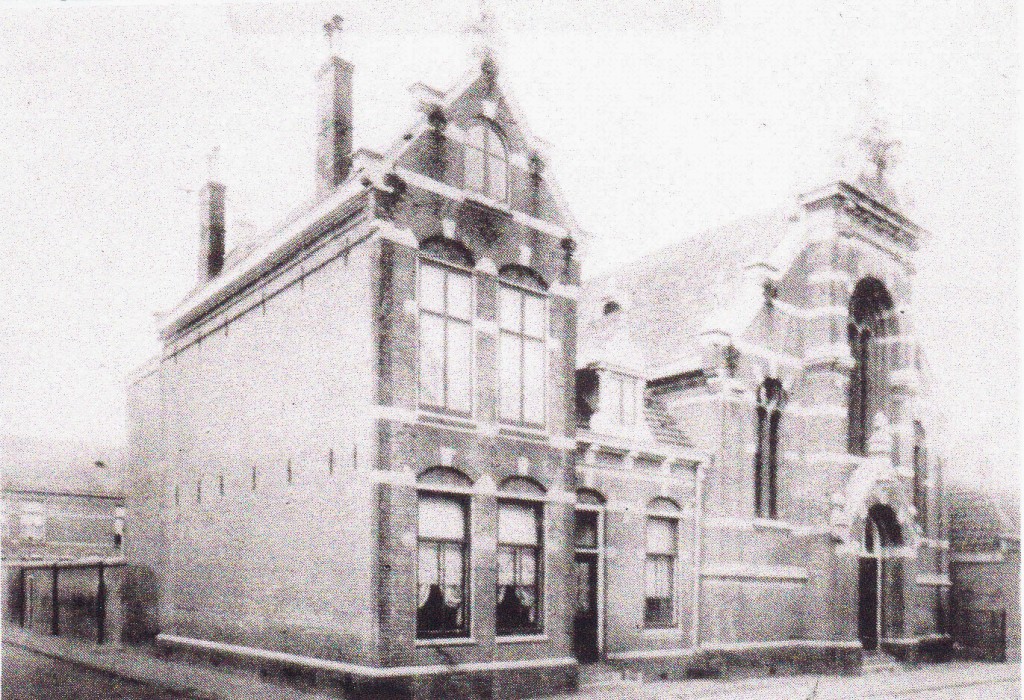

The Thalia theatre was built in 1890 as an Old-Catholic church with presbytery. When a new church was built on the Wilhelminakade, Thalia church was transformed into a basketry and fishnet-repair workshop. In 1910 the building was turned into a cinema in Art Deco-style. The movie would often be interrupted by loud announcements of the imminent departure of a fishing boat. The men concerned left the cinema to join their boats. Because German propaganda films were shown in Thalia during World War II, the theatre survived the numerous bombings. Until 1969 Thalia was used as a cinema; afterwards the building was put into use by the Civil Defence Corps. The current owners, John and Monique van Waveren, have turned it into a theatre-cum- party centre once again.

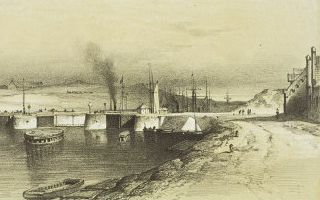

The IJ Estuary (De IJmond, IJmuiden)

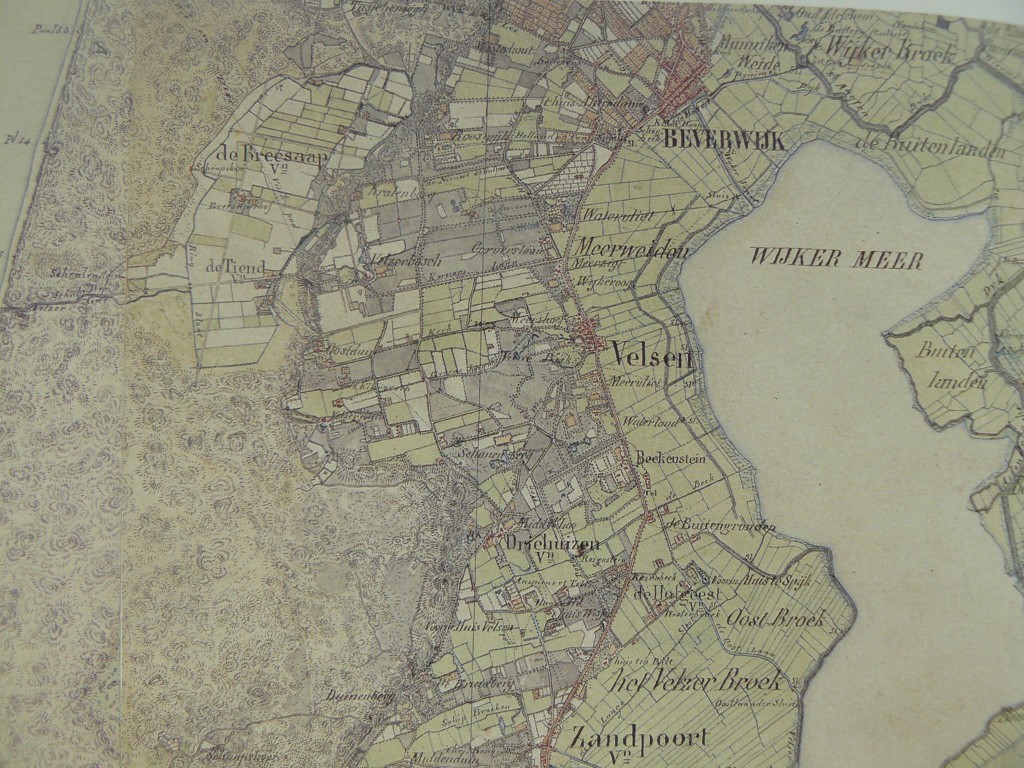

In 1848 the Amsterdam professor Simon Vissering wrote about IJmuiden in magazine De Gids: ‘an Amsterdam sea harbour lying at the estuary of a canal lying between the IJ and the North Sea’. He was way ahead of his time. On 8 March 1865 the directors of the Amsterdamsche Kanaal Maatschappij (AKM – Amsterdam Canal Company ) cut the first sod in the dunes of the estate of De Breesaap. It was an Amsterdam party, to which the local authorities of Velsen, the small town to which the De Breesaap estate belonged, were not even invited.

The heavy digging was done by common polderlabourers and navvies, who came from all parts of The Netherlands and even from as far as Germany and Belgium. On the edge of hamlet De Heide the unmarried men lived in barracks. The ‘keetbaas’ (boss) and his wife were masters of the camp and made a lot of money from selling liquor to the weary navvies. Canal workers with families had to fend for themselves. They built huts, made from faggots and clay, in the dunes or dug holes in the ground.

The construction of the locks and the digging was supervised by the English contracting firm Lee & Son. The site foremen would divide and rule: part of the labour force held a permanent appointment, the rest was hired by the day. The wages were low and there was much uncertainty among the workforce. Strikes were bound to happen and in 1886 villa Wijkeroog, the head office of the English engineers and foremen on the north side of the canal, was set on fire.

On 1 November 1876 King Willem III opened the North Sea Canal. The canal connecting Amsterdam and the North Sea by a fast route now, cut across “Holland at its narrowest part” Aboard steamer De Stad Breda the king sailed through the new locks. He signed an official charter, thus giving the Harbour of IJmuiden, the IJ estuary, its name.

The Kleine Sluis (Small lock) and the Zuidersluis (Southern lock) were opened simultaneously with the North Sea Canal. The Middensluis (Middle lock) opened in 1896 and the Noordersluis (Northern lock) in 1928. With its length of 400 metres, width of 40 metres and depth of 15 metres this was then the largest in the world.

Fortress Island

The armoured fortress with its forty-odd rooms and the impressive dome hall is the largest of the Defence Line of Amsterdam, a circle of defensive works around the capital. The Defence Line is a UNESCO World Heritage site. The fortress was built between 1881 and 1888 on the mainland for defending the North Sea Canal and the sea locks against attacks from the sea. Because the North Sea Canal was widened when the Northern lock was built the fortress became an island in 1929. It contained a variety of cannons and seven machine gun posts.

After World War I the island remained uninhabited for years. When preparing the fortress for battle during the mobilisation in 1940, Dutch soldiers came across a dilapidated mess. In the May days of 1940 not a single shot was fired. After the Dutch capitulation German soldiers settled on the island. They were ill at ease there and called it ‘Die Ratteninsel” (rat island).

For the Germans the island was a strategically important position in the Atlantikwall, which was to prevent an allied invasion along the European coast.

Koninklijke Verenigde ScheepsAgenturen (KVSA – Royal United Shipping Agencies)

One of the oldest companies of IJmuiden is the shipping agency of Halverhout en Zwart. Since 1876 the firm has offered its services to maritime companies in the North Sea Canal area. A wooden shed on the northern side of the North Sea Canal housed the first office of this shipping agency. The piece of land for its office was provided free of charge by Maatschappij IJmuiden (IJmuiden Foundation) from Messrs Bik and Arnold. It was the first private building of a maritime service company in IJmuiden. Later the company moved to the corner of Visseringstraat and Kanaalstraat. The firm is presently called Royal United Shipping Agencies Halverhout en Zurmühlen B.V. and is established at the Felison Terminal, where the ferry to England also leaves.

The English Village

The navvies and canal diggers mainly lived in De Heide, which was later called Velseroord, situated on the southern side of the canal. The English had their living quarters in the environs of country estate Wijkeroog. This community was known as The English Village. To show the English they were indispensable to digging the canal, the Amsterdam Canal Company decided to build a canteen on piles in the polder wetlands: the English Provision Stores. Liquor, smoking materials and other goodies were sold there for reduced prices. The local tax on spirits provided the municipal treasury with a piece of the pie too. Concrete casters came to live in the village as well, because they were urgently needed. They worked in the concrete factory where the blocks for the piers were cast. The blocks were transported by a narrow-gauge railway on flat wagons, pulled by a tank engine, to the piers. On the piers the concrete blocks were moved by Titan cranes. The cranes were made in England, had a radius of twelve metres and operated along rails.

Rise of the fishery

Soon after the North Sea Canal was opened fishing boats from miles around, even from England and Denmark, tried to find shelter between the IJmuiden jetties. On the piers the eternal light was burning; the new harbour lights were able to burn for twelve days and nights, thanks to a special fuel supply.

In IJmuiden a thriving fishing trade arose. Coastal fishermen from Urk, Volendam, Nieuwediep, Katwijk and Vlaardingen sailed between the piers and their smacks, cutters and luggers dropped anchor in the outer harbour. The ‘vletterlieden’ (the pilots’ predecessors) helped the fishermen to bring their catches ashore. There the fish was sold privately. With dog carts or with baskets strapped on their backs tradesmen from Egmond and other surrounding villages went to IJmuiden to buy fish. The fishmongers between them fixed the prices; they didn’t deem it necessary to involve the fishermen.

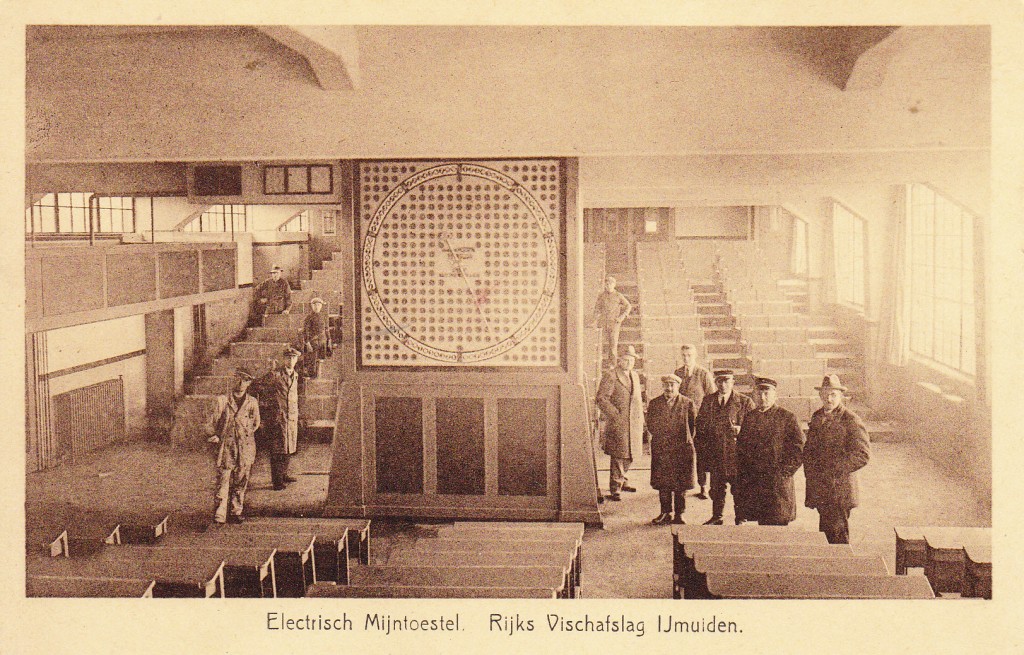

Around 1880 the fishermen agreed that private selling of fish was not satisfactory any more: the fishing trade was in need of a reorganisation. Reijer Visser from Nieuwediep organised an official fish auction near the locks. In Kanaalstraat he built a pub (café Afslag – the Auction Pub) and started a ship provisions store where fishermen could buy reasonably priced victuals. The Egmond fishmongers raised a storm of protest: no more price-fixing for them. The first fish auctioned by Reijer Visser came from the Middelharnis smack Titia Jacoba, owned by captain Maarten van Delft. Van Delft made a fantastic calculation and got 1,194 guilders for 294 cod fish, 900 haddock, 87 halibuts and turbot an 180 pieces of thornback. The government granted more licences to start a fish auction, i.e. Vischafslag Planteijdt on Ericssonstraat, and consequently there was more competition. Planteijdt later initiated the Coöperatieve Vischafslag (Cooperative Fish Auction), which was established as a protest against the government auctions.

Fishing activities were expanding. In 1885 three new jetties were built. When these proved to be insufficient the western dunes were levelled to construct the Vissershaven (Fishers Harbour), which opened in 1896. The first trawlers, called ‘trolders’ by the people of IJmuiden, were steaming into the harbour. Because the government noticed there was good money to be earned in fishing, a wooden auction was built on the head of the Vissershaven, called the Lattenmarkt (Slats market). Private auctioneers were allowed to use this auction. The government ruled that ‘it is forbidden to hold an auction any place other than designated by the harbour master in the ‘vishal’ (fish building). As a result the private auctions lost their monopoly position. A fishing war followed, won by the government. In 1899 the government established the Staatsvissershavenbedrijf (State Fishing Harbour Company), employing state auctioneers who had the exclusive right to sell fish publicly in the fish building. The first 145-metres long stone fish building was built in 1900. In the vernacular this was called “Lely’s building”.

West of the Vissershaven a small harbour for pilotage and dredging equipment was built. Along Trawlerkade the first buildings arose in 1901. Subsequently the area south of the Vissershaven was divided into practical plots and given to companies wanting to set up their businesses in the direct vicinity of the harbour. Apart from fish merchants and towing services also technical companies, supporting and supplying the shipping industry such as the predecessors of Zwart Techniek, Hera Machinebouw and Van Laar Maritiem, established their businesses here.

In 1914 it was decided to build a new harbour. It was partially situated on the same spot as the old auxiliary harbour and was accessible through the Vissershaven. 1920 saw the construction of the Haringhaven (Herring Harbour) in the present direction. In 1939 the building of the slipways south-westerly from the Haringhaven was started and in 1950 two new slipways in the Haringhaven were completed.

Ice factories

Until around 1900 fish were preserved by filling them with salt; from then on ice was used for this purpose. Firm S.J. Groen was the first to build a large ice warehouse with cold stores, called Mercurius, at the corner of Zeestraat (later called Frögerstraat) and Visseringstraat. In the summer the ice was imported from Norway; in the winter the owners of the estates Velserbeek and Rooswijk permitted ice being taken from their frozen ponds. Many ice factories followed and some years later factories such as NV IJsfabriek IJmuiden, IJsfabriek De Noordpool en NV Kristalijsfabriek Groenland, south of the Vissershaven, made artificial ice. NV IJsfabriek, later called Koelhuis IJsvries from 1911 established on Sluisplein, was the first ice factory in the vicinity of the fish building. During the first years only ice was made, but after World War I the company specialized in freezing fish, eggs, bulbs and fruit. The modernization of its machinery led to a 200 – ton ice production a day. Later the modern Koelhuis IJsvries was built on Kanaalstraat and in 1955 ice factory and cold stores were brought under one board of directors, under the name of Verenigde Koelhuizen en IJsfabrieken NV.

Paper factory Van Gelder

In 1986 Pieter Schmidt van Gelder established a paper factory, as part of Van Gelder en Zonen (1784), in Velsen along the North Sea Canal. It was one of the first companies in Velsen. The name Crown was added in 1963, as a result of making cardboard for punched cards in cooperation with the American paper factory Crown Zellerbach. In 2015 Crown en Van Gelder employ 280 people and produce 220,000 tons of paper per year for printers, labels and special packaging

Bik and Arnold expand IJmuiden

Even before the opening of the North Sea Canal the first houses were built, which was the beginning of IJmuiden. These first residents were civil servants, for whom in 1875 a row of lockkeepers houses were built near the lock. Head engineer Justus Dirks from the Amsterdam Canal Company asked seven-year old Alida Smakman, the assistant lockkeeper’s daughter, to lay the first stone. Mayor Enschedé and the Velsen town council were watching while Alida and her father laid the first stone.

The Bik family and the descendants of this well-to-do patrician family played an important part in the development of IJmuiden. In 1851 brothers-in-law Adrianus Bik and Jan Willem Arnold bought De Breesaap estate for one million guilders. In 1863 part of it was given to the Amsterdam Canal Company for digging the North Sea Canal. Messrs. Bik and Arnold were entrepreneurs and pioneers in heart and soul, showing true social involvement. In 1876 they established the Burgerlijke Maatschap (Civil Partnership), later called Maatschappij IJmuiden (IJmuiden Foundation), in which the part of De Breesaap south of the canal (355 acres) was placed. The area was levelled for building activities and was the foundation of IJmuiden. In 1877 the Foundation presented a modest development plan for housing, industry and fishery. The plan was accompanied by ‘regulations concerning the building of houses and the hygiene thereof’

Financed by Jan Willem Arnold the first forty numbered working-class houses were built on a site not far from the lock. Although built with the best intentions, the neighbourhood and its shabby houses soon became a notorious slum, called ‘The Forty’. In 1897 the houses were occupied by the first working-class families, most of whom thought they were better off than before. Mainly fishermen from Egmond lived in The Forty”. The entrance to the dwellings was through Hoeksteeg, between Prins Hendrikstraat and Zeestraat (later Frogerstraat). The kitchen had a surface area of one square metre and some box-beds could only be slept in with pulled up knees. A privy was placed outside the houses and inhabitants had to fetch water from the pump near the entrance of this neighbourhood.

The development plan of the IJmuiden Foundation showed streets in straight lines, which were connected with Kanaalstraat. A new neighbourhood was built: the new town of IJmuiden was booming; the industrious pioneer spirit accompanied by a wind of change.

IJmuiden railway station

Before the construction of the railway between Velsen and IJmuiden an omnibus-service, a large horse-drawn carriage with full-length seats, ran between Velsen railway station and Hotel Nommer Eén on Kanaalstraat in IJmuiden.

From 1867 the train from the Hollandse IJzeren Spoorweg Maatschappij (Dutch Iron Railway Company) connected Haarlem and Uitgeest, via the Velserspoorbrug: a large swing bridge near the present paper factory Van Gelder. It was not until 1883 that the construction of the railway line to IJmuiden was under way. For the section IJmuiden – Velsen part of ‘the Hoge Berg’ was levelled. At first a little railway station with a wooden platform was built, near the locks (Annastraat). In 1886 the line became a double track. The fish transport made demands too and after the completion of the Vissershaven the fish merchants insisted on a station near the harbour. Railway station IJmuiden, situated on Stationsplein at the bottom of Oranjestraat, opened in 1899. The fish train had its own station and could be loaded behind the fish building via the fish bridge.

The IJmuiden railway was closed down in 1983, but was still used for refrigerated fish transport. In 1995 the station was demolished.

IJmuiden Grandeur (IJmuiden aan Zee)

Many cherished the thought that IJmuiden would soon be a stylish tourist spot. In 1887 Hotel Nommer Eén was built at the corner of Oranjestraat – Kanaalstraat: ‘the only building with a second floor’. The hotel was a meeting place for shipowners and fish merchants and served as a cultural and community centre. When the railway line was first built it also served as a buffet for the train passengers, until in 1899 the station was built. Jacob List, who bought the hotel from Hugo Jacob Werkhoven, made it very prosperous. In 1943 the hotel had to be demolished, by order of the German occupying forces; its last owner was Gerardus Milne.

Short after Hotel Nommer Eén was built a speculative citizen of Amsterdam built a second hotel, which had to be more distinguished, more beautiful and more comfortable: Hotel Willem Barendsz. The hotel was intended for housing the luxury passengers from the mail boats and Suez ships. In good weather you could see the Westertoren in Amsterdam from the dome on the roof.

Of course many a day tripper and even foreign tourists came to look at the giant lock. The luxury tourists, however, sailed on to Amsterdam. The large hotel rooms remained empty and the hotel became dilapidated. The only way to make a little money was to rent out function rooms to the rising number of religious communities on a Sunday. Pilots and ‘vletterlieden’ used the dome as a watchtower. Before the building was eventually pulled down, it had been used by the Boon brothers as a livery stable.

The Visserijschool (Fishery School)

In 1905 the private “Vereeniging Visscherijschool IJmuiden” (Association Fishery School IJmuiden) was founded. This school trained skippers, first mates and engineers because ‘something had to be done about training these lads if the fishing industry was to have fresh and new blood in its fishing fleet’. The Fishery School could use a class room in School B on Oranjestraat and two old pilot boats. The first headmaster – teacher taught fourteen pupils from 6 to 8 o’clock in the evening.

Because of financial difficulties the town council took control over the Fishing School in 1911. After being temporarily housed in the ‘Klapschool’ on President Krügerstraat, the school moved to a new building at the corner of Kompasstraat and Havenkade in 1916. In 1952 the name was changed into ‘Gemeentelijke School voor Visserij en Scheepvaart’ (Municipal School of Fishery and Shipping Trade) and since 1981 it has been called ‘School voor Zeevaart en Techniek” (Nautical and Technical School). In 1988 the school moved to a new building on Sluisplein with again a different name: ‘Nova College Maritiem Instituut IJmond”. (Nova College Maritime Institute IJmuiden)

In 1989 a foundation was set up to preserve the old school building and to turn it into a museum. More than seventy IJmuiden volunteers partook in the restoration. In 1994 Minister Hedy d’Ancona of Welfare, Public Health an Culture opened the Zee- and Havenmuseum (Sea and Harbour Museum).

Hoogovens (Steelworks)

In 1917 H.J.E. Wenckebach presented his plan for a Dutch steelworks. The ‘Committee for establishing a steel and roll works in The Netherlands’ preferred IJmuiden to Rotterdam because of the firm subsoil. The first phase saw the realisation of two blast furnaces, a coke-oven battery, an inner and outer harbour, a railway yard, a power station and a by-products plant for cleaning the coke-oven gas.

The industrial complex that was thus developed also processed the residues into useful products. The by-product plant cleaned coke-oven gas out of coal tar, which was subsequently used as fuel in its own power station or delivered to neighbouring towns as city gas. In 1924 the Phoenix Brick Factory, which turned furnace slags into bricks, opened its doors. Also the Maatschappij tot Exploitatie van Kooksovengassen (Company for the Exploitation of Coke-oven gas – MeKog) made fertilizer from slags; the power station used rest gases. In 1930 Cement Factory IJmuiden (Cemij) started to turn slags into cement; paper factory Van Gelder used Hoogovens steam.

In 1931 Hoogovens was expanding further: processing its own pig iron was done by producing cast iron pipes by means of a self-developed casting process, followed by the construction of a plate mill according to the Siemens-Martin process and a steel plant. Hoogovens had thus become an integrated steel works and was recognized as a national basic industry. The first shares in Koninklijke Nederlandse Hoogovens en Staalfabrieken (Royal Dutch Blast Furnaces and Steel Plants) were quoted on the Amsterdam Stock Exchange on 21 October 1939. After several mergers and take-overs the name of the company has been changed into Tata Steel IJmuiden.

1920 – 1930

At the beginning of the twentieth century the fishing trade was becoming more regulated. Despite strikes and other setbacks a number of bona fide fishmongers established themselves in IJmuiden. After World War I had started it was tumultuous within the fishing trade and new names worked their way up. Many of these fishmongers originated from Egmond aan Zee, being the core of the IJmuiden fishing trade. They did not just buy and sell fish, but they also started owning herring luggers and exporting salted herrings.

In the interbellum IJmuiden got into decline. The economic recession caused a depression in the fishing trade. Because of the German inflation trade with the hinterland ground to a halt; the trawlers stayed idly in the harbour, thus affecting the fishing trade and causing the fishermen to go on strike. When in 1933 the shipowners revoked the collective agreement and proposed a fifteen percent wage reduction, the IJmuiden Federation announced a big strike among the fishermen. This strike lasted from 3 January until 11 July and is the longest in the history of the fishing industry. Emotions were running high, but eventually the actions were undermined by infighting and all efforts proved to have been to no avail.

The conditions aboard the ships were wretched and caused another strike in 1936. This time the workers did win, but it did not do them much good, because of the crisis. The fishing trade did not give up, however, and found new markets in Czechoslovakia and France. In due time the fishing trade slowly recovered and the so-called haddock boats sailed for the fishing grounds again.

National socialism, promising a better future, cropped up in The Netherlands too. In 1939 mobilization was proclaimed and IJmuiden awaited a dire lot: when World War II broke out everything that had been built was to be destroyed.

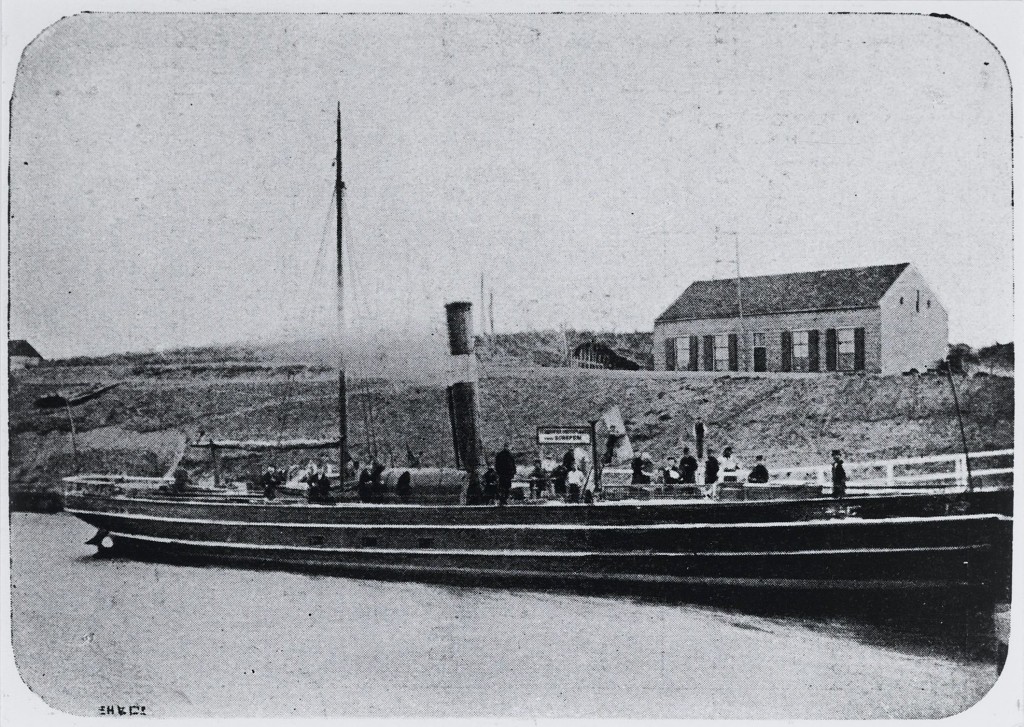

Japie Overzet (the Ferry of Japy)

For a few pennies Jacob Visser brought people from the Harbour Head to the beach by ferry, called Japie Overzet (Japie Ferry) in the vernacular. In 1928 he bought his first towboat, Alberdina, and two years later the powerful Neeltje followed, which he used for towing coal barges through the IJmuiden locks. For towing the heavy coals, coming from the Limburg mines, strong boats were needed. Later Jacob Visser also had a towing service near the Vissershaven.

During World War II trade was slack. Fishermen still at sea when the war broke out were given orders to sail for the nearest English port; the steam trawlers, lying in the Vissershaven, had to make preparations to cross over to England. In the estuary large ships were sunk to deny the Germans access to the harbour and locks, thus enabling only small fishing boats to sail in or out.

After the war Jacob Visser resumed his coal barge towing trade and because of the booming fishing industry towing services were much in demand. He bought several new tow boats: Triton (1949), Thetis (1956) and Argus.

In 1968 Jacob Visser sold the company to his employee, Ben Iskes. His son Jim Iskes, who trained as a first mate at the Nautical and Technical School, is the manager of this tug towage and salvage company nowadays.

Buried in Old IJmuiden

Because IJmuiden was growing rapidly de Vereniging IJmuidens Belang (Society for IJmuiden Community Interests) wanted to make a cemetery, which the IJmuiden Foundation and the town council arranged for by deforesting and levelling the southern part of the De Breesaap Estate. Former landowner Jan Braam was appointed overseer/gravedigger in 1896; in which year the cemetery saw 48 burials.

The entrance to this Westerbegraafplaats (Western Cemetery) is through Kerkstraat, which used to be a sandy path. The hearse had to pass a deep gully and even the railway track. A strong team of horses was needed to get the hearse uphill, through the sand. Railway men used to put planks on the track to enable the hearse to pass and the slope was made passable with flattened fishing baskets.

It often happened that the horses refused to negotiate the steep slope. After requesting the vicar to walk on ahead, the coachman, yelling and swearing, then spurred on the horses.

Over the gully a wooden footbridge was built in due course, to be replaced later by a small concrete bridge. In 1930 the town council had the present Juliana bridge built in Amsterdam School style.

Atlantikwall, field of fire and evacuations (Second World War)

Pre-war IJmuiden, with Willemsplein at its centre, was a pleasant town until World War II broke out in 1940. The jetties were bombed, Jewish refugees tried to flee Europe via IJmuiden and the Dutch Royal Family were brought to England by destroyer HMS Codrington. The Dutch government had the North Sea Canal estuary blocked by sinking ships, among which passengers ship Jan Pieterszoon Coen. The port remained open for small vessels.

In 1942 German troops built a defence line from Norway to Spain: the famous Atlantikwall, with IJmuiden as a strategic ‘Festung’ (fortress). Around IJmuiden barriers were made, such as bunkers, anti-tank pits and mine fields. IJmuiden became a ‘Sperrgebiet’ (prohibited area) and the town was vacated. The Germans also constructed fields of fire in IJmuiden and Velsen-Noord to position their anti-aircraft guns against a possible allied overland invasion, demolishing hundreds of houses in the process. In 1942 en 1943 people sometimes were forced to leave their houses within 48 hours and even had to organise their own transportation. These inhabitants took refuge somewhere within the town or outside, even as far as Friesland. Only people with an ‘Ausweis” (work permit) were allowed to enter the area.

The harbour area in Old-IJmuiden was the operating base for the Kriegsmarine (navy). A large part of the harbour was used for moorings for the Schnellboote (torpedo boats); aimed at attacking allied convoys along the English coast. The Germans built a Schnellboot-bunker in the Haringhaven and an even bigger one near the semaphore, where the traffic-control was situated. Most of both harbours and fishing buildings were destroyed during bombings of the Schnellboot-bunker.

At the end of the war Old-IJmuiden was in ruins. The buildings that were not completely demolished were heavily damaged by the many bombings of the harbour area. The total of destroyed buildings amounted to 3,190 houses, two churches, nine schools and 159 other buildings. Many more were damaged: 4,600 houses, ten churches and 363 other buildings. The old IJmuiden was never going to be the same again; many inhabitants of IJmuiden longed for the pre-war conviviality.

No post-war reconstruction for Old-IJmuiden

After the war Old-IJmuiden was a sad and dilapidated place. Everywhere were empty spots, such as the completely wiped out police station and bandstand in what used to be Willemsplein. The Koning Willemshuis and Hotel Nommer Eén on Kanaalstraat, Café Cycloop on Prins Hendrikstraat: everything was bombed or demolished. Only the Gebouw voor Christelijke Belangen (Building for Christian Interests) on Enchedéplein, the old Mercurius on Breesaapstraat, Café Afslag, the old Planteijdt auction on Kanaalstraat and the Bell Telephone building near the old lock were still standing.

Most of the reconstruction was done in East-IJmuiden and not in Old-IJmuiden. The few still-existing houses became more and more run down, because no maintenance was ever done. “The old nest by the sea” had become well nigh uninhabitable.

Mayor Kwint had been in contact with architect Willem Dudok before the war had even finished. It was his job to give IJmuiden a new face. This is indeed what he did, but only for East-IJmuiden, however. To commemorate the tragic war events he designed Plein 1945, where the new town hall was built. From then on the town council was not established in Velsen anymore but in IJmuiden. Old-IJmuiden was destined to become an industrial estate.

Dismal and damaged IJmuiden was recovering slowly. Families, whose fathers had left for England by trawler in 1940, were reunited, fishing boats, confiscated by the Germans, sailed again en the fishing buildings were rebuilt. The industry, such as Hoogovens, bombed heavily during the war, recovered too. Many people were not able to go back to Old-IJmuiden and went to live in East-IJmuiden, later in Duinwijk.

Urban renewal

As late as 1962 the town council devised a development plan for Old-IJmuiden. The area west of Oranjestraat was destined for small-scale industry. East of Oranjestraat was to become a residential area with new twelve-story apartment blocks. Most of the ramshackle buildings as far as Koningsplein were to be demolished.

The inhabitants protested: they thought the character of their neighbourhood was about to change too much. They set up Committee Old-IJmuiden, which aims were to keep the original street pattern and to restore the houses that were still fit to live in. In 1973 a compromise was reached: no more grand-scale demolition, but on Bloemstraat and S.P. Kuijperplantsoen three-story apartments blocks did arise. In spite of this houses on Schoolstraat and Generaal De Wetstraat were pulled down, as was the Groen van Prinsterer School on Koningsplein and the Roman Catholic Gregorius church on Kanaalstraat. In 1979 a new housing estate was built in the demolished area, followed by 42 new dwellings on the ‘new’ Willemsplein.

Heated discussions took place during town council meetings about the demolition plans for the villa’s on Kanaalstraat, especially about villa Nooitgedacht, built in 1900 as villa Tosari. It had been the domain of squatters for years but at the end of the eighties the villa, like community centre De Brulboei (The Foghorn) across the street, was eventually demolished by court order. Subsequently the new housing project was refused a building permit, however, because the site appeared to be situated within the Hoogovens noise zone.

At the beginning of the nineties the government designated Old-IJmuiden as a social renewal area; a neighbourhood getting more money and attention from the local authorities. Not until 1996 and 2001 did building start on Kerkstraat – Kanaalstraat, followed by new housing projects on Bik- en Arnoldkade and Duinstraat.

A modern seaport

The IJmuiden harbour is a dynamic port on the North Sea Canal estuary and is always accessible without any obstacles. The open seaport has a good reputation in the field of storage and transhipment of fresh and deep frozen fish, offshore, ferries, cruises and as well as in the field of assembling and constructing offshore wind farms. Until 1989 the seaport was owned by the state: the Staatsvissershavenbedrijf (State Fishing Harbour Company). In that year the seaport was privatized: Minister Kroes from Transport and Public Works signed the deed of conveyance to Seaport IJmuiden PLC. This is a private company, which now owns the harbours and the IJmuiden fish auction.

One hundred and fifty small companies in the harbour area partook in a € 5.3 million investment initiative, called the BOS-group. Entrepreneurs were charged reasonable prices when buying the land their premises were built on, provided they bought shares in the new company.

Maintenance was overdue, so the first tasks Sea Port IJmuiden PLC set themselves were modernizing the fish auction and investing in the harbour area. In 1990 the Trawlerkade and Leonarduskade northwest of the Middle Harbour area were realized and in 1991 the fish auction introduced the mobile auction clock, which heralded the end of oral sale. In 1994 the Dutch Fish Auction IJmuiden did its first test with phone auctioning, operating by means of telephone lines. From 2008 the auction has used the Pefa-auction system via the internet.

In 1994 near the Harbour Head the Felison Terminal was built. At first the Scandinavia Seaways ferries to Norway and Sweden docked there. From 1998 the DFDS Seaways have operated a daily service to Newcastle in England.

In 1999 the foundation stone was laid for the so-called Third Harbour. It was meant to cater for companies lacking in space to expand in the present harbour and for the coastal trade, which is an alternative for the clogged roads of the Netherlands. The new IJmond harbour was finished in 2004 and is now developing into an operating base of building wind farms off the Dutch coast and wind farm Eneco Luchterduinen. Since 2012 it has also been a major cruise ships terminal.

As of 2009 a metamorphosis is taking place in the Middle Harbour area. Reconstructing the area between Vissershaven and Haringhaven is part of a grand-scale project, enhancing the position of IJmuiden as ‘a transfer table for deep frozen fish’. Completion of this renewal project is due in 2016.

Town and Environment

From the Town and Environment-project emerges that improving the quality of life in Old-IJmuiden is a major issue in the twenty-first century. West of Oranjestraat, near the harbour, parts of the former, redeveloped industrial estate has been transformed into a new residential area. On the eastern side, where the villa’s are too, old neighbourhoods are being renovated. During the sixties in the area between Oranjestraat and Koningsplein many of the original buildings were replaced by galleried flats and home zones. Because of this most of the old street pattern has disappeared.

In the new urban development plan conservation of the present historical buildings and reconstruction of the old, rectangular street plan are the keynotes. The characteristic environment, the views, the locks, the fishing harbour and its small-scaleness have been an inspiration for the urban development plan.

In the middle of the neighbourhood the authentic Thalia Theatre has taken its prominent place again on a yet to be constructed square and the White Theatre in the former PEN power station has also become a cultural meeting point.

The other special buildings in the area, such as the church on Helmstraat and the Engelmundus church on Wilhelminakade are in need of extra attention, as is Koningsplein.

By reconstructing the former street pattern the view of the harbour and the North Sea Canal should be experienced in the whole area.

The new premises will consist of small-scale, detached houses. Along the North Sea Canal and the harbour buildings of varying height can be built. The old buildings and the small-scale area are making Old-IJmuiden an attractive place, where living, working and recreation go hand in hand.

Experience Old-IJmuiden

Projects like Town and Environment and Urban Renewal have been started to improve the quality of life in Old-IJmuiden. Businesses causing (noise) pollution have been moved or cleaned up and old houses have been demolished. The Harbour Head has been completely renovated because of the arrival of the ferry service to England and by establishing Sea Port IJmuiden a modern dock industry has been created. Government and market players are building new houses for several target groups and are restoring the old street pattern. The Thalia Theatre, the White Theatre, the Nautical and Technical School, the Sea and Harbour Museum and Fortress Island give the neighbourhood an important cultural and educational boost. The elderly may live in residential homes such as Breezicht and W.F. Vissershuis and the local residents can meet in community centre De Brulboei. The redevelopment of Old-IJmuiden is coming to a standstill, however, partly because of the economic crisis and major attention should be given to the issue of social cohesion.

Harbour, sea, fishery, the canal and locks are connecting factors for Old-IJmuiden. Many residents earn or used to earn their money in these industries or work across the canal at “De Hoogovens”. These people can tell a story or two about working and living in a unique part of IJmuiden. Stories we should not forget and which have to be shared with the younger people growing up in the neighbourhood as well as new residents. Stories connect people and provide the area with an identity of its own. Stories keep people connected with the past, bring unity and create new ideas for developing Old-IJmuiden. By recording Old-IJmuiden life stories and passing them on through all kinds of activities people will come together and Old-IJmuiden is going to be a better place to live in. The neighbourhood will retrieve its character and will be back on the map again.